Open Hostility

Most employees, despite how they might feel, keep their negative thoughts about their boss and/or their employer under wraps. When an employee decides to go openly hostile, separation is just a matter of time.

Grousing

Human beings are a dissatisfied lot, most of them finding things to criticize even when their job is generally pretty good. They complain about fairness, expecting their employer to achieve a degree of evenhandedness that even their parents couldn’t achieve. They carp about the “stupid” decisions their boss makes, not appreciating how the imposition of resource and time constraints make optimizing every choice an impossibility.

Mostly, these criticisms are communicated in quiet whispers or, better yet, saved for the nightly dinner table at home.

Every once in a while, however, an employee will take them public in the workplace.

A new car?

During a particularly stressful time period – I was in the midst of laying off employees due to a particularly steep seasonal decline in the business I was managing – I took delivery of a new car. The car was a little extravagant, a bright red convertible, of the type that demanded to be noticed. Timing was hardly ideal, but the car had been ordered during a substantially better time and I’d been waiting for delivery for nearly a year.

A short time afterward, a trusted employee informed me that there was a “new rumor” running around divisional headquarters – for every fifty people I laid off, the company would buy me a new car.

I initially wrote the comment off as a clever quip, deciding it just “blowing off steam” and probably came out of frustration over the layoffs. But the story wouldn’t go away, and after a while it seemed to be gaining in credibility (people will believe almost anything if it’s bad). It didn’t take much effort to trace the “rumor” back to one particular employee. He was, in fact, fervently and loudly repeating the “story” to anyone that would listen.

I’m not sure what I did to anger this particular person. Not sure exactly what inspired his little “campaign.” Perhaps it was simply having a ready audience of frustrated peers that were wearied by the layoff process, and one in front of whom he could look shrewd and bold. Or maybe I laid off his best friend. Whatever the reason, he was not holding back.

A few weeks later I found out he was quitting. To take a job with our biggest competitor. In the same role he had in our company, one that had access to sensitive strategic information. A short time later, I also discovered he had taken a substantial amount of company proprietary information with him.

That cast the story in a new light.

When the car rumor was offered, he had undoubtedly already made his decision to leave. Possibly, he was already interviewing with the competitor. It emboldened him, and changed the normal calculus that would have otherwise offered enough discouraged to suppress his outrageous behavior.

Actively Disengaged

Later in my career, I became familiar with a way of classifying employees into three groups – Engaged, Disengaged, and Actively Di-engaged. This was accomplished with a survey tool, but understanding the categories, a manager could do a pretty good job of categorizing just based on observations. Of course, the final category is the worst – those employees that are actually working against management.

There are actively disengaged employees in pretty much every organization of size. Between 10 and 30 percent, in fact.

Why don’t they leave?

Employees become actively disengaged for several reasons. They may actually work for a terrible boss (employees join companies and leave bosses – a commonly taught management rubric). The “deal” they expected from the company may have somehow unfavorably changed during the course of their employment. Or, in many cases, disengagement comes from inside the dissatisfied employee themselves – they would likely not be happy anywhere.

For whatever reason, active disengagement is the signal that company and employee should part company. So why don’t these employees leave voluntarily?

Actually, there are many reasons. They might not have other accessible opportunities. They may be extremely risk averse, and not want to trade bad for what might turn out to be worse. They may even think their agitation will change things for the better.

As a manager, it is important to do what you can to find such people and encourage them to move on – sometimes with a boot in the backside, depending on how outrageous their behavior has become.

Openly hostile employees have a large, negative impact on the business. They complain to their peers, and anyone else that will listen, bringing them down. They undermine the company’s initiatives. They take up an inordinate amount of management time. They even drive good people away.

What to do?

As a manager, you need to be on the lookout for the actively disengaged. Experience has taught me that attempting to rehabilitate these employees is almost always a waste of time. Instead, you should encourage them to find new opportunities. If they are unwilling to depart on their own, don’t hesitate to fire them. The fewer hostile employees on your roster, the more likely you are to successfully get your objectives accomplished, and the more likely you are to have a close-knit, high performing team. 26.1

Other Recent Posts:

- Treat People with Kid Gloves or Hit them with a Hammer?

- Clock Watchers Redux

- At the Bottom of the Hill is… the Inventory Account

- Don't Count on Your Casting Vote

- The Way it Ends

- When to Walk Away from a Deal

- How many Execs does it take to Screw Up a Deal?

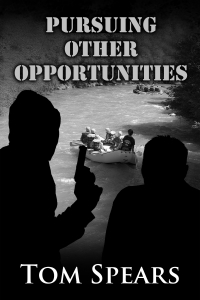

If you are intrigued by the ideas presented in my blog posts, check out some of my other writing. Novels: LEVERAGE, INCENTIVIZE, DELIVERABLES and HEIR APPARENT. Coming soon -- PURSUING OTHER OPPORTUNITIES

Non-Fiction: NAVIGATING CORPORATE POLITICS

This is a B&W version of the cover of my new, and soon to be released novel, PURSUING OTHER OPPORTUNITIES. This story marks the return of LEVERAGE characters Mark Carson and Cathy Chin, now going by the name of Matt and Sandy Lively and on the run from the FBI. The pair are working for a remote British Columbia lodge specializing in Corporate adventure/retreats for senior executives. When the Redhouse Consulting retreat goes horribly wrong, Matt finds himself pursuing kidnappers through the wilderness, while Sandy simultaneously tries to fend off an inquisitive police detective and an aggressive lodge owner.

My novels are based on extensions of my 27 years of personal experience as a senior manager in public corporations. Most were inspired by real events.