A popular saying holds that “bad stuff” rolls downhill. There are varying opinions, however, as to what lies at the bottom of the metaphorical “hill.” Some say it is their business, their department, or them, personally.

When it comes to manufacturing companies, my experience is that the “bad stuff,” at least when it represents a “sin” of some type, whether intentional or accidental, eventually finds its way into the inventory accounts.

There are several reasons for this:

- Inventory accounts are usually large in the typical manufacturing company. If there’s going to be unseen mistakes, problems from sloppy practices, or downright fraud, it’s easiest to hide them in a big bucket. Inventory is usually that bucket.

- Inventory is complicated. Sure, raw material is pretty simple, normally including only the costs of things you purchased. Work in Progress (WIP) and Finished Goods (FG) include labor and overhead. It is in these accounts you can find all kinds of things improperly handled and/or buried.

- There are lots of adjustments. As the costs and quantities of things change, there are variances, write ups, write downs, quantity adjustments, etc. All of these things are subject to mistakes or outright abuse.

- Nobody likes checking it. Inventory counts are painful and expensive. Evaluating standards is even worse.

I think it is safe to say that clean, well-managed inventory accounts are the hallmark of a well-managed manufacturing company. You can tell a lot about a manufacturer by carefully looking at this one account.

This is particularly true when you’re making an acquisition, or evaluating a potential partner.

Who’s got the inventory?

A joint venture company I was once involved in went through a traumatic change of management. When the new General Manager was in place, one of the first things I asked him to do was to look over the financial practices of the company (his background was accounting) with an emphasis on how inventory was handled.. We quickly zeroed in on two practices that ultimately ended up costing us millions.

The company took on construction-type jobs, and would accumulate costs associated with those jobs in a “Work in Progress” inventory account. During construction of the job, they would recognize a percentage of the revenue for the total project, and expense the costs associated with that revenue percentage based on their original job estimate. When the job was finally completed, it was then “closed out” and the accumulated costs were compared to what had been expensed, and everything was “trued up.” If the original estimate had been accurate, everything would be fine at the closing stage.

But that wasn’t how things always went.

We discovered that there were a number of jobs that should have been closed out. Some had been in a state of “suspended animation” for many months. As it turned out, former management knew these jobs were going to result in large losses when they were closed, and in an effort to avoid “taking the pain” they just left them sitting in inventory.

The ultimate cost was hundreds of thousands of dollars. And that wasn’t the biggest inventory problem.

This same Joint Venture also owned millions of dollars of rental equipment. The problem was the equipment was never returned to the company’s offices after being used by the customer. It was, instead, simply left at the customer’s site and a new “warehouse” was defined where it was “stored.” Sometimes these “warehouses” would sit for years without being re-deployed. While the company have records of what was originally rented to the customer, no one was visiting the remote “warehouses” to perform counts or check on the condition of the equipment.

Technically, the rental equipment was a “fixed asset,” but it was managed just like the other inventory accounts in the company. Once we went looking for this rental inventory, no one was terribly surprised to find much of it was not where it was supposed to be. Or it was only partially there. Or it was unusable.

That one cost us millions.

Why this rarely come to light

Most inventory problems build up over time. Once someone begins to suspect they are present, it takes an act of pure will to deal with them.

No one will thank you for discovering it. Senior management will often look for a reason to parcel out blame. Why did this happen on your watch? Who was responsible? What are you putting in place to make sure it never happens again?

Etcetera, Etcetera.

Many managers know about problems, but they simply ignore them. “These problems were here when I arrived, and I’m not taking the hit for them,” appears to be a common attitude.

Normally, it takes a change of management to bring them to light, and then only during that “golden window” when everyone will agree the new manager didn’t contribute to the problem. Even if the new manager is determined to clean up the mess, he or she is likely to meet plenty of resistance from long-term staff as they are still likely to catch plenty of blame for not dealing with the issue earlier.

Flushing the toilet

I ended up firing a long term manager at a remote manufacturing plant a few years ago. The reasons for the termination didn’t have anything to do with what we found buried in the inventory account when the new guy took over.

The plant was large, complex, and old, so I wasn’t surprised when “new guy” told me there was, literally, millions of dollars in obsolete inventory at the site, items the previous manager had simply swept aside, unwilling to deal with them.

The revelation came at a time when I had been in my job for three years. There was, predictably, plenty of criticism leveled at me. Ultimately, this particular incident was a significant contributor to me losing that job.

Of course, the vast majority of the problem occurred well before my watch began. I suppose I could have been more aggressive in looking when I’d first stepped into my job….

But no one would have thanked me for doing so.

Conclusion

A long career in the management of manufacturing companies has repeatedly taught me that few, if any, manufacturing companies have clean, well-managed, inventory accounts. Expect to find bad practices, sins of the past, and even the results of fraud, if and when you start digging.

But make sure you know how the results will be received before you look too closely. 25.3

Other Recent Posts:

- Don't Count on Your Casting Vote

- The Way it Ends

- When to Walk Away from a Deal

- How many Execs does it take to Screw Up a Deal?

- Redialing the Deal

- Buy Low

- Businesses Always Look Simpler from the Outside

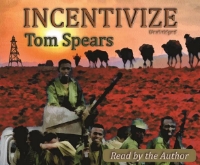

If you are intrigued by the ideas presented in my blog posts, check out some of my other writing. Novels: LEVERAGE, INCENTIVIZE, DELIVERABLES and HEIR APPARENT. Coming soon -- PURSUING OTHER OPPORTUNITIES

Non-Fiction: NAVIGATING CORPORATE POLITICS

To the right is the cover of the audio version of INCENTIVIZE. This novel takes the reader on a trip through some of the most remote areas of the volatile Horn of Africa, as the story follows EthioCupro's attempt to get rid of a pesky auditor -- permanently.

My novels are based on extensions of 27 years of personal experiences as a senior manager in public corporations.