Of course, compliance with rules and regulations is a part of the task of both managers and individual contributors within any company, large or small. Such compliance requirements run through pretty much every position in the organization. For a shop floor employee, there are many such rules that must be followed, from OSHA safety regulations to work rules, to HR policies. People working in the offices usually comply with different but equally obtrusive procedures. Examples of these would include things like the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, SEC regulations of various sorts, EEOC plans and guidelines, and hundreds of internal controls and guidelines.

Unfortunately, regulatory compliance contributes almost nothing to actually accomplishing the mission of the company – it’s all about staying out of trouble. In fact, it can often become a distraction, soaking up time, energy, and bandwidth due to its potentially punitive nature.

Some managers (particularly those in jobs like “Corporate Attorney,” “Human Resources Manager,” and increasingly, “Finance”) can find their jobs have morphed into full time compliance roles, essentially taking them out of managerial mix and turning them into an internal policeman.

Big firm, Big target

Large firms have a lot to lose if they fail to comply with laws and regulations. Reputations are of critical importance to high profile organizations (admittedly, not all large firms fit into this category) and any misdeed, no matter how seemingly innocuous, can become cannon fodder aimed at their good name. They live in fear that their reputation will be damaged by some small act of non-compliance, and this non-compliance will have a large, detrimental impact on the organization at large.

Even large firms that aren’t particularly high profile (Danaher Corporation as compared to Apple, for example) know that it doesn’t take much to attract the media’s attention. If they want to stay low profile, they need comply

As a result, nearly all large firms “invest” in compliance in some fashion. And, in my opinion, nearly all large firms at least to a degree become “compliance obsessed.”

For example, several of my employers have had their own, in house, Environmental Departments. These departments exist for the sole purpose of making sure the organization knows the environmental rules and strictly follow them. Every site was audited at least annually. Where any non-compliances were identified (and believe me, there were few because nobody wanted to expend time and money on the recovery side of this equation) we received extra, punitive attention. We even had programs to assess failure risks and put preventative measures in place to stop spills/emissions before they occurred. In a twenty factory network that I managed for one employer, we easily put 4-5 man-years of effort into this compliance effort every year – and that was in a year when we didn’t have a violation.

Is this good? Or bad?

In one sense, compliance is a societal good of the type that we can’t count on companies to perform on their own. The government must step in and enforce such rules, otherwise large firms would fly by the seats of their collective pants (much like the smaller firms, which I’ll describe below).

Large companies can easily create much more damage or bigger problems than their diminutive counterparts when not in compliance. It wasn’t small banks, after all, that created the mortgage meltdown of 2008 – it took the big behemoths to bring our financial system to its knees.

Society benefits at the expense of the company, with a heavier burden generally falling on larger companies.

In a “compliance obsessed” company, it is easy to slip from “managing the future” of the business into “staying out of trouble.” In large firms, there are almost always a few resources that are committed to compliance. Some companies even have “ethics” or “compliance” officers, people dedicated to uncovering and pursuing non-compliances. These positions are often high up in the corporate ranks in order to give the internal and external appearance that the company takes non-compliances seriously. These people are powerful. Respected.

Their work – their mere presence – sends a funny message to the managerial staff, I can assure you.

The message: work on improving the business and implementing (or developing) strategy, but never, ever, ever get caught in a situation where you are guilty of non-compliance.

Checking boxes easily becomes an end unto itself, and it is easy for the company to tilt in the direction of “compliance” over “achievement.” And that’s when the corporate inefficiency factor really starts to kick in.

Export obsession

While working for one employer, we had a violation of a U.S. embargo rule. The problem (as near as I was able to determine) was innocent enough – a Canadian division of the company mistakenly sold to a Canadian company who was on a U.S. blacklist (for being a Cuban trading partner). The rules surrounding complying with U.S. embargo law are complicated in the extreme, and the Canadian subsidiary didn’t realize their customer was blacklisted.

What followed was a complete revamping of our entire sales process, which required the development of new forms, new approval procedures for sales, and multiple checks and balances to insure we didn’t again make the same mistake. Even in my smallish part of the company, we invested thousands of hours making all these “improvements.”

The effort definitely took away from other things management could have been doing. At the time, we were in the process installing a new IT system, and the Embargo Compliance effort probably slowed down implementation by a couple of months (as compliance demanded new reports, new checklists, new data entry screens, and none of that could wait for the new system to be installed). It was a classic example of Compliance trumping Management.

Flying under the radar

In smaller organizations, a lot of this simply doesn’t get done.

Small businesses lack the expertise and the resources to become compliance experts – at least not like you would see in a large firm. In smaller companies, we are dependent on the knowledge of compliance each experienced employee brings with them (although we sometimes rely on outside experts, when absolutely necessary) to keep us out of trouble.

When it comes to things related to other external compliance efforts like environmental, SEC, EEOC, employment law, taxes, OSHA, etc., we tend to skimp.

Past experience counts for a lot: If you’ve been fined by OSHA, compliance there looms larger. If you’ve been sued because of age discrimination, probably you’ll be more careful about who you lay off next time there is a downturn. But if no one ever complained about the “paint odor” emanating from your building, you probably aren’t going to spend a lot of time checking EPA regulations.

This behavior undoubtedly results in many more violations. If the government wanted to catch more polluters, discriminators, safety violators, etc., they would certainly find them in the ranks of smaller firms. Such a compliance drive would, however, probably strangle many of these businesses when they are competing against the big boys.

An aspect of one of my jobs was to work on acquisitions of small firms – a “roll-up” strategy. It was rare to find an acquisition candidate that wasn’t out of compliance with government regulations, at least in one area if not multiple spaces. Some of the violations were willful – companies cutting corners because they were willing to roll the dice. My staff and I often spent a lot of time figuring out how the target company could clean up their compliance problems before a deal could be struck. Sometimes the deals died over compliance hurdles as there was no way my employer could tolerate the risks implicit in the small firm’s behaviors.

Summary

The government seems to think observing and investigating big firms for non-compliances gives them a bigger bang for the buck. And they’re probably right.

As a result, big firms commit a greater proportion of resources to compliance – despite their size advantages – and can easily find themselves tilting into “compliance campaigns” when something goes wrong, further exacerbating this inherent disadvantage of “bigness.”

The resulting situation gives small companies a leg up when they are competing against gargantuan rivals – just one of the many ways that corporate inefficiency in big firms is an Anergy (the opposite of a “Synergy”).

Posts in the “Corporate Inefficiency” Series (Chronological Order)

- Classic: Corporate Inefficiency

- Classic: Corp Inefficiency, Sunk Costs

- Classic: Corp Inefficiency, Groupthink

Posts in the “Behaviors Managers Hate” Series (Chronological Order)

- Classic: Behaviors Managers Hate, Overview

- Classic: Behaviors Managers Hate, Fairness

- Classic: Behaviors Managers Hate, Blinders

- Classic: Behaviors Managers Hate, Entitled

- Classic: Behaviors Managers Hate, Performance Cluelessness

- Classic: Behaviors Managers Hate, Business Cluelessness

- Classic: Behaviors Managers Hate, Blaming

- Classic: Behaviors Managers Hate, Hiding

- Classic: Behaviors Manager hate, Suggesters

- Classic: Behaviors Managers Hate, Clock Watchers

To find other blog posts, type a keyword into this search box, or check my Blog Index…

My LinkedIn profile is open for your connection. Click here and request to connect. www.linkedin.com/in/tspears/

If you are intrigued by the ideas presented in my blog posts, check out some of my other writing.

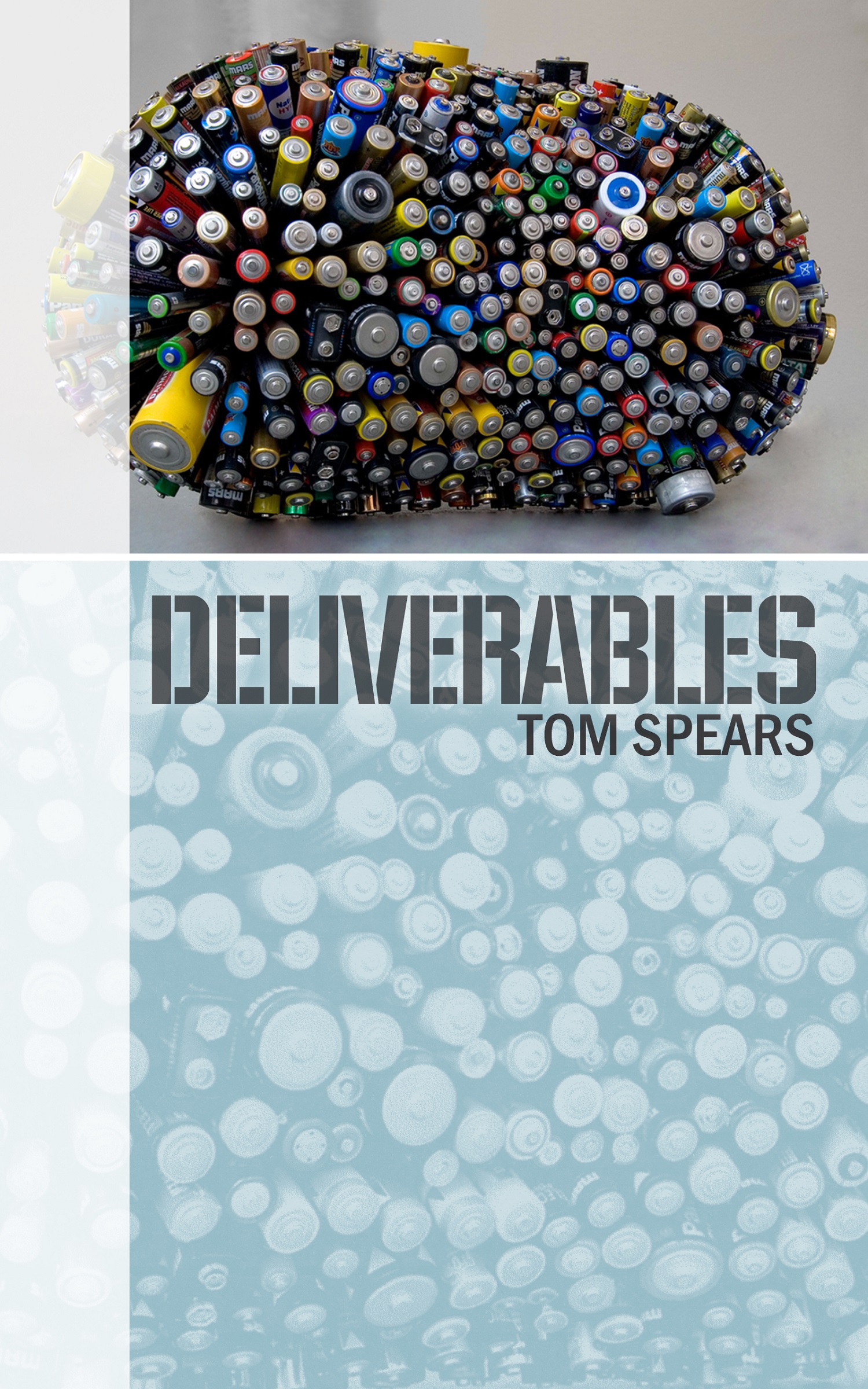

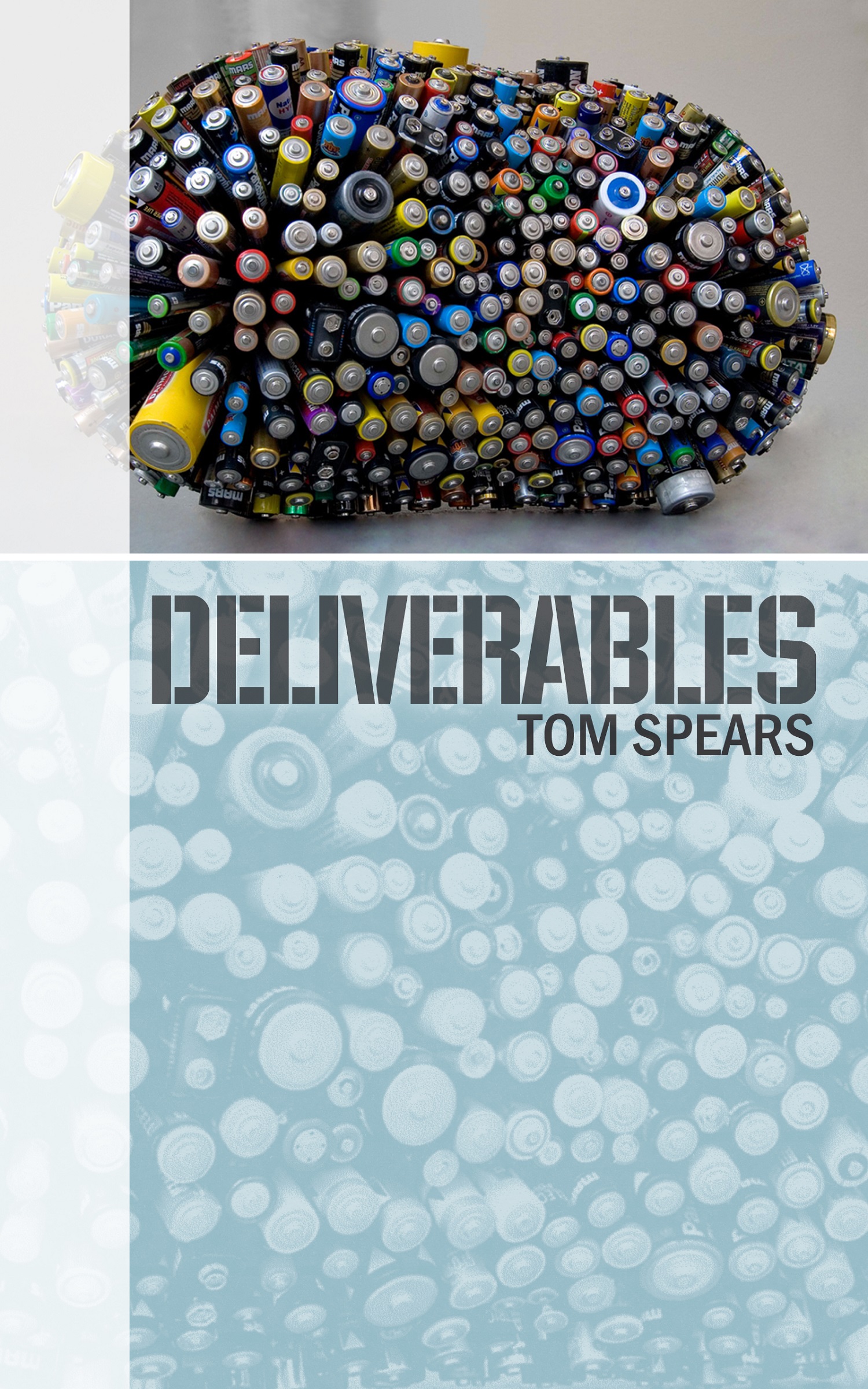

Novels: LEVERAGE, INCENTIVIZE, DELIVERABLES, HEIR APPARENT, PURSUING OTHER OPPORTUNITIES, and EMPOWERED.

Non-Fiction: NAVIGATING CORPORATE POLITICS

To the right is the cover for DELIVERABLES. This novel features a senior manager approached by government officials to spy on his employer, concerned about how a "deal" the company is negotiating might put critical technical secrets into the hands of enemies of the United States. Of course, things are not exactly as it seems....

My novels are based on extensions of 27 years of personal experience as a senior manager in public corporations.