Consistent direction delivered consistently over the long haul.

That's what I've always seen as the chief hallmark of a successful business strategy. And while there are other important elements to a successful strategy (such as: Simple, understandable messaging that is easy to communicate and presents an effective rallying cry, or internal and external alignment of all resources, etc.) if your strategy has consistency and longevity, it is much more likely to be successful.

The opposite of consistency and longevity is what I like to call "Flip-flopping."

One type of flip-flopping that is commonly seen in corporations is popularly called: "Flavor of the Month" management. In this type of strategic error, the company adopts a series of popular management techniques, attempting to put 100% of organizational attention behind the idea, while essentially discarding whatever was it's predecessor. For example, when a company spends a year or two developing "Six Sigma" programs, moves on to "Lean Manufacturing" while forgetting "Six Sigma," and then a couple years later engages in "Total Quality Management" while ignoring both of its predecessors, they are partaking in "Flavor of the Month" behavior.

If the company simply spent six consistent years developing their "Six Sigma" (or any one of the three) program, they almost certainly would achieve much greater impact than can possibly be accomplished by engaging in the flip-flopping behavior. At the outset of any major strategic change in company direction, management should expect to commit for at least a decade, recognizing that nothing short of an emergency should be the basis for changing.

So why doesn't that happen?

Probably the biggest reason is that managers change jobs. A new senior executive will reach into her toolbox and grab something that worked for her in a prior position. Respect for the existing strategy being pursued by the company will most likely be minimal. In fact, if the perception exists that the prior incumbent "failed" their strategies will likely be seen as "damaged goods" as well.

The other common cause is a bit more insidious. Most managers have long ago figured out that it is better to be busily "doing something" than accepting what is already in motion. The need to make a visible impact drives ambitious managers to constantly tinker.

Tinkering when not appropriately sized or timed, as I've mentioned above, is often bad.

And, of course, size matters. The larger the company, the more pressure there is for managers to make a name for themselves. This makes them much more likely to add, subtract, and alter all kinds of strategies, activities, and programs. The flurry of activity can quickly and subtly undermine the enthusiasm and motivation of employees.

In one of my division president positions, I came into the job having had good success with Lean Manufacturing in my previous position. I immediately discarded the Six Sigma program that had been in place for more than a year, and shifted focus. At the time this seemed perfectly reasonable to me, but later I came to realize my flip-flop had resulted in a one-step-forward, one-step-backward situation from the point of view of the employees. Getting them enthusiastic about Lean was difficult. When my successor then shifted gears to focus on "Brand development" it must have been even harder. And what was the justification of all these changes, really? Did Lean deliver much better results than Six Sigma could have? No. Was neglecting Lean and moving on to Brand Development the key to a better future? It didn't turn out that way. In fact, the division was behind where they would have been once the impact of multiple changes in direction was taken into account.

As bad as strategic flip-flops are, flip-flopping on individual decisions is even worse. This goes beyond the draining enthusiasm and substitution with sarcasm, instead confusing employees and destroying their credibility with their constituents.

In one of my assignments, I worked on an acquisition that my boss flip-flopped on four times. Each time, I was expected to halt forward progress on the deal and go back and renegotiate points that the other side felt were already resolved. With each flip-flop cycle, I lost credibility with the sellers, until the last time I simply refused to be the messenger.

I quit that job a few weeks later.

While I can understand "buyer's remorse," or even later recognizing an element of the agreement wasn't what we originally thought we had. In this case, however, the flip-flopping manager simply couldn't make up his mind. Not only did I feel he was failing to stick by his prior decisions, but I also felt he was indirectly micromanaging the negotiations. The result was both demotivating and irritating.

I'd be hard pressed to describe a single managerial flip-flop I've ever heard of that led to improved outcomes. The only possible exception I'll admit to would be a strategic flip-flops that occurred when a program was clearly failing. Come to think of it, however, I'm not sure I can think of a real example of that!

As a manager, you should constantly be on the watch flip-flops, always asking yourself if the step back you are about to take is going to be fully compensated for by the new direction you are trying to put in place. And if you find yourself flip-flopping on individual decisions -- just stop. Delegate authority, set direction, and then step back. If you feel you can't do this, there is either something wrong with your subordinates or your own management technique. 22.1

Other Recent Posts:

- On Being Sued

- Keeping Secrets

- Dragged Down By Seeking Revenge

- The Wisdom of Those Who Went Before You

- Where Loyalty Truly Lies

- Sold on a Story

- Different Isn't Necessarily Better

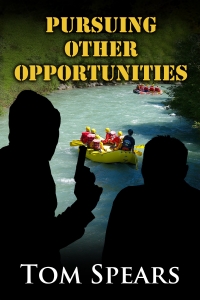

If you are intrigued by the ideas presented in my blog posts, check out some of my other writing. Novels: LEVERAGE, INCENTIVIZE, DELIVERABLES and HEIR APPARENT. Coming soon -- PURSUING OTHER OPPORTUNITIES

Non-Fiction: NAVIGATING CORPORATE POLITICS

This is the cover of my new, and soon to be released novel, PURSUING OTHER OPPORTUNITIES. This story marks the return of LEVERAGE characters Mark Carson and Cathy Chin, now going by the name of Matt and Sandy Lively and on the run from the FBI. The pair are working for a remote British Columbia lodge specializing in Corporate adventure/retreats for senior executives. When the Redhouse Consulting retreat goes horribly wrong, Matt finds himself pursuing kidnappers through the wilderness, while Sandy simultaneously tries to fend off an inquisitive police detective and an aggressive lodge owner.

My novels are based on extensions of my 27 years of personal experience as a senior manager in public corporations. Most were inspired by real events.